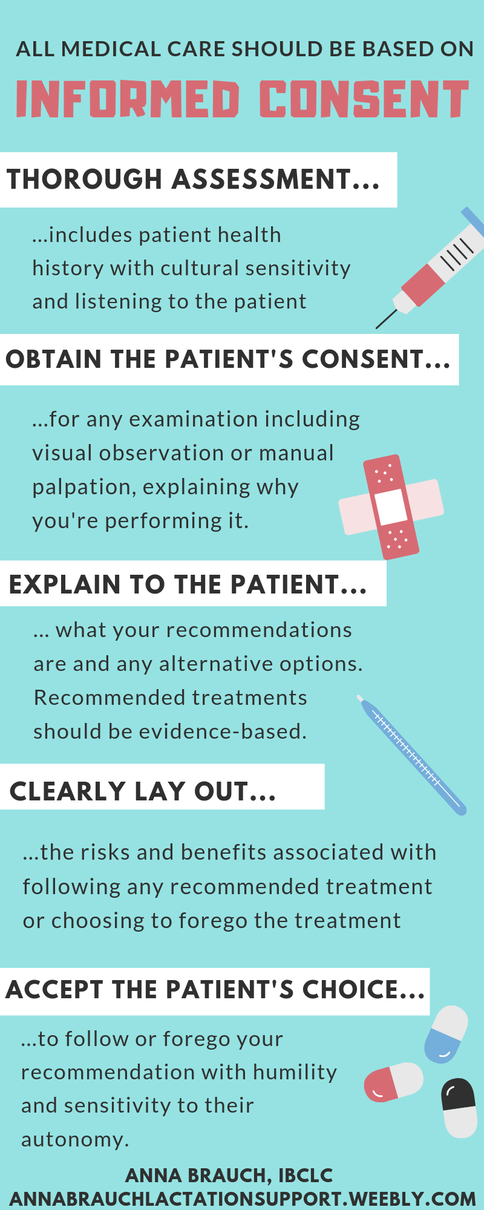

Recent experiences, both as a practicing medical professional and as a person who seeks medical care for myself and my family from time to time, have me thinking about informed consent today. In the United States, our medical establishment has a serious problem with informed consent. Medical providers themselves seem uninformed about the risks and benefits associated with the treatments they recommend to their patients, or at least unwilling to share that information with their patients for whom it is so very pertinent. People seeking medical care often end up ascribing to therapies without knowledge of risks, research, side effects, and what alternative options are available to treat their issue. This is an issue that I strongly feel affects every person accessing medical care in the US. Unfortunately though, as with many other basic needs people need to access including food and housing, medical care seems to be least accessible for those most marginalized communities like black, indigenous, and people of color communities, queer and trans folks, and economically disadvantaged people. Studies have shown, especially in regards to reproductive care, that those folks are the least likely to be listened to by doctors and to be treated with autonomy and respect in clinical settings. A provider's goal should be to inform the patient about the best course of action to treat or prevent illness or injury, and to accept the patient's response to that information with humility and flexibility, allowing for cultural differences and personal preferences that will, at times, fail to align with the provider's prescribed therapies. Providers should seek further education and deeper understanding of varying therapies for patients from broad backgrounds, and should continue to do so throughout the entirety of their career, as research advances, new therapies are developed, and social and cultural changes occur within communities. Basing medical care in a model of informed consent with careful ethical and cultural considerations makes medical care more accessible and gives autonomy back to the patient. In every single visit with every family I support, I try to continually seek feedback from the patient about how my recommendations would work for their family and whether they are comfortable with the interventions I'm performing. I take verbal as well as visual cues to inform myself about whether the patient still feels comfortable with an intervention and whether further discussion should happen before my examination continues. What are visual and verbal consent cues? I begin with asking for verbal consent for the specific intervention I'd like to provide, with information about why I would find it valuable. For example, "I'm going to wash my hands, and then I'd like to check your baby's mouth for anything unusual that might be making it hard for her to maintain her latch. Is that alright?" If the parent gives verbal consent, I carry out the exam while checking in for visual cues: has the parent stopped engaging with me? Do they appear nervous? Have they agreed verbally to my recommendation but then didn't follow through on instructions necessary to follow through with it, such as undressing themselves or their baby or moving into the position I've suggested? If so, then I stop the examination and move back into discussion. For example, I may have asked a new parent if she would like me to observe her nursing her baby and she said yes, but then looked away, got quiet, and did not begin nursing her baby. Often at this time I gain more information about the family's goals or values, finding that they have agreed out of nervousness, a lack of confidence, or a desire to please me as a provider, but that the recommended therapy is uncomfortable for them. Perhaps the mother has already decided to discontinue breastfeeding but felt nervous about admitting it to me for fear that she would be judged or reprimanded. The following conversation will include an acknowledgement that the family has verbalized a new goal or value with me and that I can make a new recommendation that supports the new goal, sometimes with more information about how the new goal will change outcomes for the parent and child and any new risks or benefits associated with the new treatment plan. Imagine if every interaction with a healthcare provider included this consideration and attention. The medical professional community should be seeking to provide the best possible care with the lowest possible incidences of physical and emotional trauma, unnecessary intervention, and misdiagnosis due to poor communication skills. Informed consent is one part of the puzzle in providing supportive, evidence-based, and culturally sensitive care that empowers the patient and prevents trauma in the healthcare setting.

3 Comments

11/17/2023 10:03:24 am

Eurosilicone Calf Implants ... On this site, skin grafts (allografts) , anti-cellulite corsets , liposuction (liposuction) corsets , arch bar splint , calf prosthesis . There may be changes in prices according to the method of the transaction to be made https://turkeymedicals.com/fat-transfer/calf

Reply

6/2/2024 05:01:34 am

Definitely stable, brilliant, fact-filled facts in this article. Ones threads Do not sadden, and this absolutely is true in this article likewise. People generally produce a motivating understand. Would you say to Now i am fascinated?: )#) Sustain the great articles or blog posts.

Reply

7/1/2024 03:06:35 am

I am just genuinely thrilled to come across this great site along with does get pleasure from looking at valuable content put up below. Your concepts in the publisher ended up being wonderful, cheers to the talk about.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorI believe in the importance of knowledgeable, supportive professionals and peers to make natural infant feeding a success. Archives

March 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed