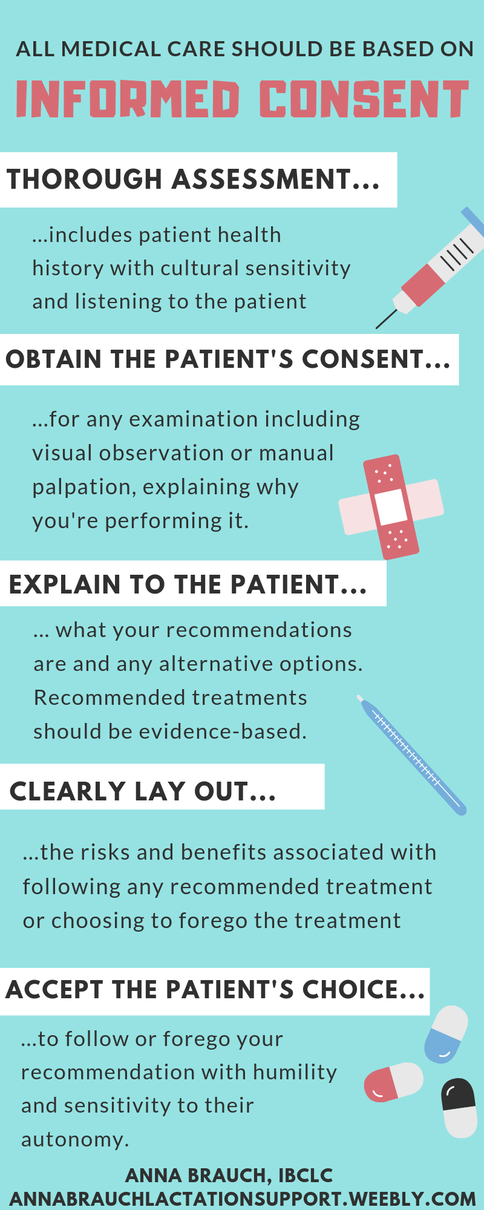

Recent experiences, both as a practicing medical professional and as a person who seeks medical care for myself and my family from time to time, have me thinking about informed consent today. In the United States, our medical establishment has a serious problem with informed consent. Medical providers themselves seem uninformed about the risks and benefits associated with the treatments they recommend to their patients, or at least unwilling to share that information with their patients for whom it is so very pertinent. People seeking medical care often end up ascribing to therapies without knowledge of risks, research, side effects, and what alternative options are available to treat their issue. This is an issue that I strongly feel affects every person accessing medical care in the US. Unfortunately though, as with many other basic needs people need to access including food and housing, medical care seems to be least accessible for those most marginalized communities like black, indigenous, and people of color communities, queer and trans folks, and economically disadvantaged people. Studies have shown, especially in regards to reproductive care, that those folks are the least likely to be listened to by doctors and to be treated with autonomy and respect in clinical settings. A provider's goal should be to inform the patient about the best course of action to treat or prevent illness or injury, and to accept the patient's response to that information with humility and flexibility, allowing for cultural differences and personal preferences that will, at times, fail to align with the provider's prescribed therapies. Providers should seek further education and deeper understanding of varying therapies for patients from broad backgrounds, and should continue to do so throughout the entirety of their career, as research advances, new therapies are developed, and social and cultural changes occur within communities. Basing medical care in a model of informed consent with careful ethical and cultural considerations makes medical care more accessible and gives autonomy back to the patient. In every single visit with every family I support, I try to continually seek feedback from the patient about how my recommendations would work for their family and whether they are comfortable with the interventions I'm performing. I take verbal as well as visual cues to inform myself about whether the patient still feels comfortable with an intervention and whether further discussion should happen before my examination continues. What are visual and verbal consent cues? I begin with asking for verbal consent for the specific intervention I'd like to provide, with information about why I would find it valuable. For example, "I'm going to wash my hands, and then I'd like to check your baby's mouth for anything unusual that might be making it hard for her to maintain her latch. Is that alright?" If the parent gives verbal consent, I carry out the exam while checking in for visual cues: has the parent stopped engaging with me? Do they appear nervous? Have they agreed verbally to my recommendation but then didn't follow through on instructions necessary to follow through with it, such as undressing themselves or their baby or moving into the position I've suggested? If so, then I stop the examination and move back into discussion. For example, I may have asked a new parent if she would like me to observe her nursing her baby and she said yes, but then looked away, got quiet, and did not begin nursing her baby. Often at this time I gain more information about the family's goals or values, finding that they have agreed out of nervousness, a lack of confidence, or a desire to please me as a provider, but that the recommended therapy is uncomfortable for them. Perhaps the mother has already decided to discontinue breastfeeding but felt nervous about admitting it to me for fear that she would be judged or reprimanded. The following conversation will include an acknowledgement that the family has verbalized a new goal or value with me and that I can make a new recommendation that supports the new goal, sometimes with more information about how the new goal will change outcomes for the parent and child and any new risks or benefits associated with the new treatment plan. Imagine if every interaction with a healthcare provider included this consideration and attention. The medical professional community should be seeking to provide the best possible care with the lowest possible incidences of physical and emotional trauma, unnecessary intervention, and misdiagnosis due to poor communication skills. Informed consent is one part of the puzzle in providing supportive, evidence-based, and culturally sensitive care that empowers the patient and prevents trauma in the healthcare setting.

3 Comments

1/7/2019 0 Comments January 07th, 2019Hand expression is a useful tool for parents in various stages of lactation. A milk removal technique used alternatively or in combination with mechanical pumping and direct feeding at the chest, hand expression is worth learning for a variety of situations:

Techniques for hand expressionWash your hands before beginning. You can collect your expressed milk in a bowl or wide-mouth jar. Some parents have had success expressing directly into a milk storage bag or bottle by putting a funnel in the top of the container! Encourage a milk let-down (if you've given birth or lactation is established) by massaging your chest, interacting with your baby, looking at pictures of baby, or using a visualization technique that relaxes you and encourages oxytocin in your body. Place your hand on your chest with your fingers under your nipple and your thumb above it, about an inch and a half away from the nipple. Press your hand toward your chest wall. Roll your thumb and fingers toward your nipple while maintaining pressure towards your chest wall. Repeat this motion until milk appears, then continue in a rhythmic motion, moving your hand around your chest to drain all the ducts. With practice, you can become an expert at the art of hand expressing!

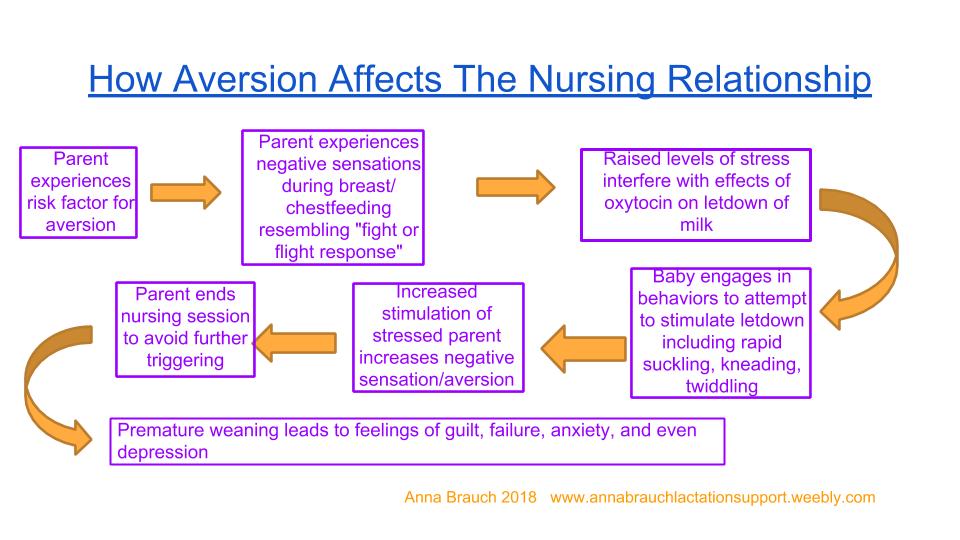

There is very little understanding or research on breastfeeding aversion, also known as breastfeeding agitation or nursing aversion, but it is a real condition with complex physiological and emotional causes. As a nursing parent myself who experienced aversion for several years over the course of my nursing relationship with my two children, I searched desperately for answers to why this was happening to me and for solutions that would enable me to continue nursing my kids until they self weaned at a biologically normal age. Nursing aversion is characterized by a negative reaction to the sensation of breastfeeding ranging from mild to very intense. Parents’ descriptions of their aversion or agitation include irritability, anger, rage, a “skin crawling” or creepy crawly feeling, or an intense urge to run away or to harm their child when nursing. The feeling almost always begins upon latching or shortly after beginning the nursing session and ends directly upon delatching the child, although some people struggling with aversion may even be triggered by thinking about nursing, seeing other parents feeding their children, or having their breasts or chest touched by their children or anyone else. Some parents experience aversion every single time they nurse, while others may find that their agitation appears while feeding at night, at certain times during their menstrual cycle, or at other specific times. Aversion differs from nipple pain or Dysphoric Milk Ejection Reflex (D-MER). It also stands apart from postpartum depression or anxiety or other mood disorders, although they can coincide and PPMDs may be a risk factor for developing aversion. Due to the lack of knowledge and research about aversion in the breastfeeding field, medical providers may misdiagnose a parent’s reports of aversion symptoms as one of these other conditions, and treatment may not be very effective, which puts the breastfeeding relationship at risk. There appear to be a number of risk factors that increase a breastfeeding or chestfeeding parent’s likelihood of experiencing aversion, including:

If you're not very familiar with nursing during pregnancy or tandem nursing, the book Adventures in Tandem Nursing by Hilary Flower is a great resource for understanding the complex issues that are unique to the experience including nipple pain, nursing aversion, and supply changes. It's an apt way to gain insight into the variety of concerns and experiences of pregnant nursing parents and is the only publication that includes first-person descriptions of nursing aversion ranging from mild to intense. Aversion caused by nursing an older child may be caused or exacerbated by the emotional reaction of having very urgent and frequent requests for nursing when it isn’t desired by the parent. As you can imagine, this is more likely to happen with a toddler or older child who is a very avid and frequent nurser. With children like these, there can often be an imbalance of the parent’s needs and the child’s, and some children are quite persistent with grabbing at a parent’s chest, pulling their shirt down, and attempting to nurse against a parent’s wishes. This may be triggering for any parent, and especially one who is sensitive to stress or conflict, or is a survivor of past physical, sexual, or psychological abuse. I’ve developed a flow chart to help professionals and advocates understand the physical and emotional experience of aversion or agitation. The increase in stress hormones interferes with the hormone oxytocin’s role in the milk ejection reflex, simultaneously stimulating in the parent the “fight or flight” response, which is why parents with agitation report a strong urge to run away from their child or to hurt their child in some way. Lacking a letdown of milk, the nursling engages in behaviors to attempt to bring on milk letdown including rapid suckling, kneading, and twiddling, which in many cases increase the aversive feeling, and so on. For this reason it can be very difficult for a nursing dyad to overcome the challenge of aversion and it can often lead to premature weaning, which can lead to feelings of failure, guilt, anxiety and even depression in a new parent, particularly if they feel a lack of understanding about the cause of their aversion and have not received knowledgeable support with the issue. Parents who are predisposed to strong reactions to stressors and to mood disorders due to past trauma are more likely to experience extreme negative emotions if aversion leads to premature weaning. In my own experience with aversion, by far the most helpful resource I found was peer support from a La Leche League Leader friend of mine who had struggled through her own aversion. I believe peer support is one of the most helpful resources for parents struggling with aversion, and online groups can be a great place to get this support, with the network of breastfeeding and chestfeeding parents who have connected on social media. Clearly, more research is needed about this topic, so that pediatric and postpartum medical providers can also be resources for help and support. In my next article, I will discuss approaches to dealing with, treating, and overcoming breastfeeding aversion. How to address baby biting while nursing is a question that comes up regularly in my lactation support circles. Of course, it makes sense that this is a common question, because: one, all babies get teeth eventually; two, many babies like to experiment with these new things in their mouth while they're at the chest; and three, getting bit on the nipple really freaking hurts and once it happens once, a parent usually feels pretty desperate to make sure it never happens again.

The common suggestion I hear again and again, especially from peer parents in in-person and online peer support groups, is to address baby biting by taking corrective action; perhaps you could even call it punitive. Common advice I hear is "plug or cover baby's nose so she has to unlatch," and "firmly say "NO BITING!" and put your baby down on the floor and walk away quickly. I understand the rationale behind these suggestions: parents assume that, if a baby associates a negative consequence with biting, then baby will not bite. Well, it really doesn't quite work that way, and I cringe when I hear this advice being given. Here's the problem with a punitive response: it's really harsh, and it's gonna freak your baby out. I have seen such responses turn into full-fledged nursing strikes, meaning baby suddenly began refusing to feed at the chest altogether. A nursing strike isn't pleasant for anyone, and is usually a very stressful situation, especially for an exclusively breastfed baby. Nursing strikes often come as a result of a trauma in baby's world, and when that trauma happens while baby is nursing, it doesn't set baby up for a good future relationship with the chest. The punitive response also does not address the cause of the biting. Babies bite for two reasons: to relieve pain from teething, or because they're bored and want attention from their nursing parent. There are fairly obvious solutions to biting caused by teething pain: relieve the baby's pain before nursing by providing a cold toy to chew on, or frozen fruit or veggies, or rubbing a bit of ice on the gums. Biting for attention deserves more of a critical thought process to solve. Parents who follow gentle parenting theories, like those preached by William Sears, believe that a child's requests and needs (even those that are displayed with less than ideal behaviors like tantrums or biting) are valid and that responding empathically to and meeting those needs is the parent's duty, and will result in trust between parent and child and building of the child's self-esteem. So, to return to the punitive or harsh response to biting- yelling "no", setting baby down, walking away from baby- let's assess how those actions will affect trust and self-esteem according to attachment parenting models. They don't respond with empathy or consider the emotional need behind the baby's action; they don't validate the child's need or build trust between parent and child. They are the lactation world's equivalent of a time-out. So, once you've determined that your baby's biting is a way of saying, "hey, look at me, I'm down here! Play with me! I'm bored and lonely!" how do you address it? Give your baby some eye contact. Talk to your baby and play with his toes. Put your phone or book down. I get it, I do. I am an enormous multi-tasker when it comes to breastfeeding. It's truly when I get my reading, socializing, and just about everything else done. And while I am a fan of the idea that "breastfeeding meets all of baby's needs", there will come a time when your baby (just like you!) will be interested in a little more socialization during those nursing sessions. Avoid the temptation of your gadgets and duties once in a while and indulge in an intimate, fun, I've answered desperate calls from many families who are struggling with something they thought would be natural and easy: feeding the baby. As a new first-time parent, I struggled with it myself. My case, like many others, had less to do with medical obstacles to breastfeeding and much, much more to do with my perception of how breastfeeding was going compared to how I thought it should be going. I had a baby who nursed every hour, and I would have been just fine with it, were it not for the well-meaning family members and friends who admonished me not to "let him use me as a pacifier". Each time he cried out to be held, I picked him up and nursed him, and felt guilty about it, thinking I was feeding him too much.

Well, guess what? Those family members and friends were failing me. There's no such thing as nursing a baby too much. Babies are born to nurse! The problem is that our culture, having thrown breastfeeding by the wayside a few generations ago, has forgotten that babies are humans with instincts, emotions, and the ability to communicate. Our culture doesn't trust babies to know when they're hungry. Unfortunately, many parents armed with a lack of support and information get so anxious that their baby is nursing frequently that they think there must be something wrong with their milk, or their ability to make it. To these parents, one misinformed comment from a neighbor or one undereducated care provider could mean the end of the breastfeeding relationship. Here's what I mean. Baby A was born in a hospital to Mama A. Mama A knew she wanted to breastfeed exclusively, and things went great. She had a large storage capacity, and Baby A was an Olympic-level nurser, gulping down 5 ounces of milk at every feeding and nursing every three hours during the day and sleeping six hours in a row at night by one month of age. (Of course, being an exclusive breastfeeding dyad, they didn't know- or need to know- how many ounces they were getting in a feeding. We get to know this because, well, I'm making it up.) Just a few days later, Mama A's cousin Baba B gave birth to their baby, Baby B. Baba B knew they wanted to nurse exclusively, and things got off to a pretty good start. By three weeks of age, Baby B, a somewhat fussy baby with a big appetite, was nursing about every hour and a half during the day and every two or three hours at night. Baba B had a smaller storage capacity, providing about two ounces at a time, and Baby B always seemed to need both sides at every feeding. Baba B felt okay with this, although they sometimes wondered why their baby seemed to need to nurse so much more than babies they'd seen in movies and read about in parenting books. After one particularly tiring night where Baby B woke to nurse every hour or two, Baba B was having lunch with Mama A and confided in their cousin about how exhausted they were. "I don't know, Baby B seems healthy and I feel like I have enough milk, but she nurses all the time and I'm getting so little sleep! Does Baby A nurse this much?" Mama A responds, "Oh no, she's been sleeping through the night for weeks! She nurses every three hours like clockwork during the day. I think Baby B is just using you as a pacifier. Try having someone else take her for a while, or give her a Nuk to suck on and leave her in the crib so you can get some rest." A seed of doubt planted, Baba B is convinced that Baby B should be nursing like Baby A. They buy a pacifier and start sticking to an every-three-hours feeding schedule. Baby B seems fussier than ever. Baba B starts to seriously wonder if they just aren't making enough milk. After a few weeks, Baba B notices Baby B isn't peeing as much as she used to and hasn't pooped in days. They head to the pediatrician. The pediatrician weighs Baby B, whose weight percentile has dropped from the 30th percentile to the 10th. The pediatrician tells Baba B that they must not be making enough milk and should start giving an ounce of formula after every feeding. Baba B is disappointed, but worried for their baby's health and not seeing any other options, they go pick up a can of formula. What happened? Baba B and Mama A were both equally equipped to feed their babies with their bodies. They both had babies who could suckle and milk making tissue that functioned. They had two different babies with different temperaments, different appetites, and different nutritional needs. They had different storage capacities and different beliefs and anxieties. Our two nursing dyads represent the wide array of normal, healthy feeding relationships that mother nature has created. One baby may grow and thrive on 22 ounces of milk per day spread out over 8 feedings; the baby next door may get the exact same amount of milk and fall rapidly off the growth charts, meeting a diagnosis of failure to thrive. Each baby's unique needs and each parent's different capacities for milk storage are the reason that scheduled, measured feedings don't work for many families. Now imagine our story taking place in a world where natural infant feeding is the norm, and knowledgeable support is easy to find. The afternoon they're having lunch, a tired Baba B complains to Mama A about the sleepless night they had. Mama A has attended her local La Leche League group and remembers hearing about growth spurts; she has heard LLL Leaders say "watch your baby, not the clock," and she knows that on-demand nursing meets a baby's needs best. She tells Baba B, "You must be exhausted. Growth spurts are hard-it seems like she's nursing constantly, huh? You're a good parent, meeting her needs day and night." Baba B feels a little better. After a few days, the growth spurt is over and Baby B, secure and content with her needs met, surprises Baba B by beginning to sleep in four hour stretches. Two years later, Baby B is still nursing and has cute, chubby rolls proving the nutritional quality of the milk her parent once doubted was good enough. |

AuthorI believe in the importance of knowledgeable, supportive professionals and peers to make natural infant feeding a success. Archives

March 2019

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed